Vancomycin and Infusion Reactions: What You Need to Know About Vancomycin Flushing Syndrome

Dec, 15 2025

Dec, 15 2025

Vancomycin Infusion Rate Calculator

This tool calculates the minimum safe infusion time for vancomycin to prevent flushing syndrome. Based on clinical guidelines, vancomycin must be infused at 10 mg per minute or slower to avoid reactions.

Calculate Safe Infusion Time

Enter your dose and rate to calculate the safe infusion time

Important Safety Note: Vancomycin must be infused at 10 mg/min or slower to prevent flushing syndrome. This calculator shows the minimum time required based on your input. For a 1g dose, the infusion should take at least 100 minutes.

Warning: Infusing vancomycin faster than 10 mg/min significantly increases the risk of flushing syndrome. This reaction is not an allergy but a direct histamine release that can cause redness, itching, and low blood pressure.

When you get a serious bacterial infection, vancomycin can be a lifesaver. It’s one of the strongest antibiotics we have for tough bugs like MRSA. But if it’s given too fast, something unexpected-and uncomfortable-can happen. You might feel your face and chest turn red, your skin start to itch, or even feel dizzy. This isn’t an allergic reaction in the usual sense. It’s a direct, physical response to how quickly the drug enters your bloodstream. And it’s completely preventable.

What Is Vancomycin Flushing Syndrome?

For years, this reaction was called "red man syndrome." That name is outdated, offensive, and inaccurate. Today, medical guidelines call it vancomycin infusion reaction or vancomycin flushing syndrome. It’s not an allergy. You don’t need to have had it before to get it. It doesn’t involve your immune system making antibodies. Instead, vancomycin directly triggers mast cells in your body to dump histamine into your blood. That’s what causes the redness, itching, and sometimes low blood pressure.

The reaction usually shows up 15 to 45 minutes after starting the infusion. Your face, neck, and upper chest turn bright red. You might feel like you’re burning up. Itching is common. In more severe cases, you could get muscle spasms, chest tightness, or a fast heartbeat. Rarely, blood pressure drops enough to cause dizziness or fainting. But here’s the key: your lungs usually stay fine. No wheezing, no swelling in your throat. That’s how you tell it apart from a true allergic reaction.

Why Does It Happen?

It’s all about speed. Vancomycin is given through an IV, and if you push it in too fast, your body doesn’t have time to handle it. Studies show that infusing 1 gram of vancomycin over less than 60 minutes triggers the reaction in most people. In one classic study from 1988, 9 out of 11 healthy adults developed the reaction when given 1,000 mg over one hour. None of them had it when the same dose was given over four hours.

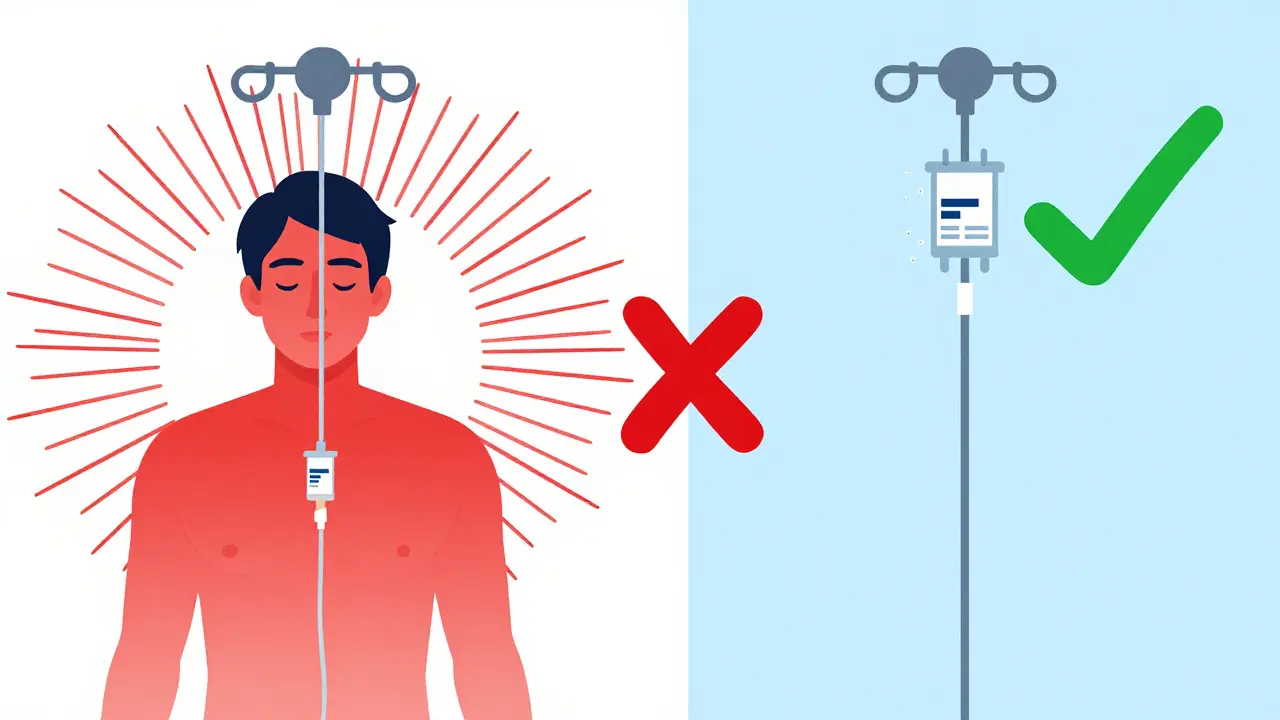

The rule of thumb? Don’t go faster than 10 mg per minute. That means a 1-gram dose should take at least 100 minutes to infuse. If you’re giving a 500 mg dose, that’s still 50 minutes minimum. Slowing it down cuts the risk by over 90%. The histamine levels in your blood spike when you rush it-and they drop fast when you slow down. That’s why the reaction gets milder or even disappears after the first few doses. Your body seems to adapt.

It’s Not an Allergy-But People Think It Is

This is where things get messy in hospitals. Because the skin turns red and the patient feels bad, nurses and doctors often label it as a "vancomycin allergy." That’s wrong. And it has real consequences. A 2021 study found that over 60% of patient records in one hospital system still used the term "red man syndrome" when documenting this reaction. That led to patients being wrongly flagged as allergic to vancomycin. As a result, they were given less effective, more expensive, or more toxic antibiotics.

At UCSF, researchers looked at nearly 200 patients who were labeled as allergic to vancomycin. Only 3% had true anaphylaxis. The rest? Most had the flushing reaction. Others had different types of skin reactions, like DRESS or Stevens-Johnson Syndrome-those are rare but serious. But the majority? Just a fast infusion.

When hospitals started replacing "red man syndrome" with "vancomycin infusion reaction" in their electronic records, the number of incorrect allergy labels dropped by 17% in just three months. That’s not just better terminology-it’s better care.

How to Prevent It

The best treatment? Don’t let it happen in the first place.

- Always infuse vancomycin at 10 mg per minute or slower. Use an infusion pump if possible.

- Never give it as a rapid IV push. That’s dangerous and unnecessary.

- Avoid giving it at the same time as other drugs that trigger histamine release-like opioids, muscle relaxants, or contrast dye.

- Don’t pre-medicate patients who’ve never had a reaction before. Giving diphenhydramine or ranitidine upfront doesn’t help and adds unnecessary side effects.

For patients who’ve had a previous reaction and need vancomycin again, slowing the infusion is still the first step. If the reaction was severe or they need the drug urgently, doctors may give an H1 blocker (like diphenhydramine 25-50 mg IV) or an H2 blocker (like ranitidine 50 mg IV) 30 minutes before the infusion. But even then, the infusion rate must still be slow.

What to Do If It Happens

If you’re the one getting the infusion and you feel flushing, itching, or warmth in your chest-speak up immediately. The nurse should stop the drip right away. Most symptoms fade within 30 minutes after stopping. If the reaction was mild, they might restart the infusion at a slower rate after 15-20 minutes. If it was severe-with low blood pressure or chest pain-they’ll monitor you closely and may give fluids or medications to stabilize your blood pressure.

Don’t assume it’s just "a bad reaction" and ignore it. Even though it’s not an allergy, it can be dangerous if it leads to a drop in blood pressure or if it’s mistaken for something worse. Always report it to your care team so it gets documented correctly.

Other Drugs That Can Cause Similar Reactions

Vancomycin isn’t the only drug that does this. Amphotericin B, used for fungal infections, can cause similar flushing through a different mechanism-by activating the complement system. Rifampin, another antibiotic, triggers reactions because its metabolites bind to proteins in your body. Even some fluoroquinolones like ciprofloxacin can cause histamine release if given too fast.

That’s why doctors don’t just look at vancomycin when someone has a reaction. They check what else was given, how fast, and whether the timing matches. If you’ve had a reaction to one of these drugs, your team will be extra cautious with the others.

Why Terminology Matters

Calling it "red man syndrome" isn’t just outdated-it’s harmful. The term has racist roots and reinforces stereotypes about skin color and medical conditions. Major medical organizations, including the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, now require the use of "vancomycin infusion reaction" or "vancomycin flushing syndrome" in all official documents.

When hospitals changed their electronic records to remove the old term, they didn’t just fix a name. They reduced misdiagnosis, improved treatment, and showed that medicine can evolve to be more respectful and accurate. Language shapes perception. And perception shapes care.

What’s the Bottom Line?

Vancomycin is powerful. It saves lives. But it has to be handled with care. The flushing reaction isn’t rare-it’s common when the drug is rushed. It’s not an allergy. It’s not your fault. And it’s 100% preventable with simple, proven steps: slow the drip, monitor the patient, and use the right terms.

If you’re a patient, ask: "How fast will this be given?" If you’re a provider, slow it down. Even if the patient seems fine. Even if you’re in a hurry. The extra 30 minutes could mean the difference between a smooth treatment and a scary, avoidable reaction.

Vancomycin doesn’t need to be a gamble. With the right approach, it’s safe, effective, and predictable.

Is vancomycin flushing syndrome an allergic reaction?

No, it’s not an allergic reaction. Allergies involve the immune system making antibodies (IgE) after prior exposure. Vancomycin flushing syndrome is an anaphylactoid reaction-meaning it’s caused by direct histamine release from mast cells. It can happen the very first time you get vancomycin, and it doesn’t require prior sensitization.

Can you still use vancomycin if you’ve had a flushing reaction before?

Yes, absolutely. Most people who’ve had a reaction can safely receive vancomycin again-just at a slower infusion rate. Slowing it to 10 mg per minute or slower prevents the reaction in nearly all cases. In rare cases where the reaction was severe, doctors may give an antihistamine before the infusion, but the rate still must be slow.

Why do hospitals still sometimes mislabel this as a vancomycin allergy?

Because the old term "red man syndrome" was widely used, and many staff weren’t trained on the difference between an infusion reaction and a true allergy. When a patient turns red and feels unwell, it’s easy to assume it’s an allergy. But studies show over 90% of these cases are not allergic. Mislabeling leads to patients being denied effective antibiotics and put on costlier, less ideal alternatives.

How long does it take for vancomycin to cause a reaction?

Symptoms usually begin 15 to 45 minutes after starting the infusion. They can also appear shortly after the infusion ends. The reaction peaks quickly and typically resolves within 30 minutes after stopping the drip. If symptoms last longer than an hour, it’s likely something else.

Are there any long-term effects from vancomycin flushing syndrome?

No. The reaction is temporary and doesn’t cause lasting damage. Even if it’s severe, once the infusion stops and symptoms resolve, there’s no risk of chronic issues. The main danger is misdiagnosis leading to inappropriate antibiotic use, not the reaction itself.

Can children get vancomycin flushing syndrome?

Yes. Children are just as susceptible as adults if vancomycin is infused too quickly. Pediatric guidelines recommend the same infusion rate: no faster than 10 mg per minute. In fact, because children have smaller blood volumes, the reaction can sometimes be more noticeable. Always use a pump and monitor closely in pediatric patients.

Souhardya Paul

December 16, 2025 AT 17:49Just had a patient last week with this exact reaction - thought it was an allergy until we slowed the drip. She was terrified, but once we explained it wasn't an allergy and just a speed thing, she relaxed. Now she’s teaching her family about it. This stuff needs to be common knowledge, not just for docs but for patients too.

Slow infusions aren’t just safer - they’re cheaper. No need for antihistamines upfront. No mislabeling. No avoiding vancomycin when it’s the best tool for the job. Simple fix, huge impact.

Josias Ariel Mahlangu

December 17, 2025 AT 04:23People still call it 'red man syndrome'? That’s not just outdated - it’s embarrassing. Medicine should be above this kind of lazy, culturally tone-deaf language. If you’re too lazy to update your EHR terminology, you’re probably also too lazy to check your infusion rates.

Stop blaming patients for reactions you caused by rushing the drip.

anthony epps

December 18, 2025 AT 07:50Wait so if you give it slow, it doesn’t turn you red? That’s it? No medicine or anything? Just… wait longer?

Andrew Sychev

December 20, 2025 AT 07:34They’re lying. This is a corporate cover-up. Vancomycin is being pushed because Big Pharma owns the hospitals. The ‘flushing syndrome’ is just a distraction. Real allergic reactions are being ignored so they can keep selling this toxic drug.

And don’t get me started on how they changed the name - that’s gaslighting. They don’t want you to know the truth. I’ve seen patients collapse after this ‘slow drip’ nonsense. It’s all staged.

Someone’s getting rich off this. And you’re being lied to.

Dan Padgett

December 21, 2025 AT 21:02You know, back home in Nigeria, we say ‘the medicine that walks too fast stumbles.’ Vancomycin’s like a chief walking into a village - if he rushes in shouting, folks get scared. But if he walks slow, smiles, greets everyone - the whole village welcomes him.

This reaction? It ain’t the drug being bad. It’s how we treat it. Slow down. Listen. Respect the process. The body knows what it needs - we just gotta give it time.

And yeah, calling it ‘red man’? That’s like naming a storm after the color of the sky. Doesn’t make sense. Doesn’t help. Just hurts.

Hadi Santoso

December 23, 2025 AT 14:37Just wanted to say - I’m a nurse in a rural ER and we switched to ‘vancomycin infusion reaction’ in our charts last year. No more ‘red man’ - and guess what? Fewer patients got flagged as allergic. One guy came back for a MRSA infection and they almost gave him linezolid because of his old chart. We had to explain it again. Took 10 minutes. Saved him $3k and a week of GI chaos.

Language matters. And so does slowing the damn drip. I’ve seen nurses rush it because they’re ‘in a hurry.’ Please. Your hurry isn’t worth their panic.

Also - yes, kids get it too. My niece got it at 8. We cried. Then we slowed it down. She’s fine now. No allergies. Just a slow IV.

Thanks for writing this. Needed this.

Kayleigh Campbell

December 25, 2025 AT 07:56So let me get this straight - we’ve known since 1988 that slow = safe, but we still have nurses rushing it because they’re ‘too busy’?

And we’re still calling it ‘red man syndrome’ because someone in 1975 thought it was funny?

And now we’re surprised patients get misdiagnosed?

Wow. Medicine is a masterpiece of human stupidity. I’m so proud.

Elizabeth Bauman

December 26, 2025 AT 09:43Who gave you permission to say vancomycin isn’t dangerous? This is a foreign drug! We used to use penicillin - clean, American-made, safe. Now we’re letting some lab-bred chemical from overseas turn people red? And you’re telling us to just slow it down?

What’s next? Letting Chinese antibiotics into our hospitals? This is why our healthcare system is collapsing - because we listen to people who don’t even know what a real allergy is.

Real Americans don’t get flushed by vancomycin. They get treated with real medicine. Period.