Idiosyncratic Drug Reactions: Understanding Rare and Unpredictable Side Effects

Nov, 29 2025

Nov, 29 2025

Idiosyncratic Drug Reaction Risk Checker

Check Your Symptoms

This tool helps identify potential idiosyncratic drug reactions (IDRs) based on symptoms and timing. IDRs are rare, unpredictable reactions that occur at normal doses and typically appear 1-8 weeks after starting medication. Early recognition is critical for treatment.

Please select your symptoms and timing to see your risk level.

Note: This tool is for informational purposes only and does not replace professional medical advice.

Most people expect side effects from medications - nausea, dizziness, dry mouth. These are common, predictable, and often listed on the label. But what if your body reacts to a drug in a way no one could have guessed? That’s an idiosyncratic drug reaction - a rare, unpredictable, and sometimes life-threatening response that doesn’t follow the rules of pharmacology.

What Makes a Drug Reaction Idiosyncratic?

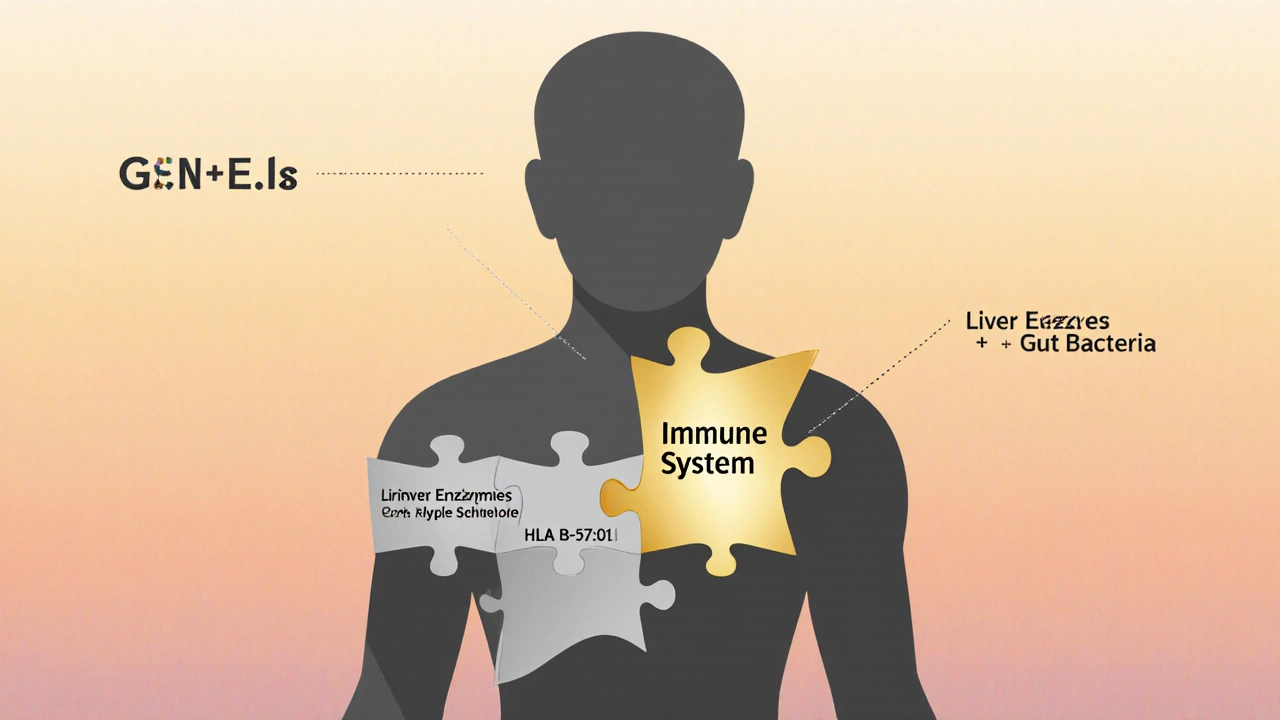

Idiosyncratic drug reactions (IDRs) are not about taking too much of a pill. They’re not even about being allergic in the classic sense, like a peanut rash or anaphylaxis. These reactions strike without warning, usually after weeks of taking a drug normally. They affect roughly 1 in every 10,000 to 100,000 people. That’s rare - but when they happen, they can be devastating. Unlike typical side effects, which scale with dose (called Type A reactions), IDRs happen at normal, prescribed doses. A patient might take a drug for six weeks without issue, then suddenly develop a fever, rash, or jaundice. The drug hasn’t changed. The dose hasn’t changed. But the body has - in a way science still doesn’t fully understand. The term "idiosyncratic" comes from the Greek word for "one’s own." These reactions belong to the individual. They’re shaped by a mix of genetics, immune history, liver metabolism, and even gut bacteria. No two cases are exactly alike. And because they’re so rare, they rarely show up in clinical trials, which typically involve a few thousand people at most. That’s why some drugs get pulled off the market years after approval - like troglitazone for diabetes or bromfenac for pain. Both caused fatal liver damage in a tiny fraction of users.The Most Common and Dangerous Types

Not all idiosyncratic reactions are the same. The two biggest categories are drug-induced liver injury and severe skin reactions. Idiosyncratic Drug-Induced Liver Injury (IDILI) is the most frequent. It accounts for nearly half of all serious drug-related liver damage. It can show up as hepatitis-like symptoms - yellowing skin, dark urine, fatigue - or as bile flow blockage (cholestasis). The liver doesn’t always scream for help. Sometimes, damage builds slowly over weeks. By the time a patient feels sick, the liver may already be severely injured. About 13% of all acute liver failure cases in the U.S. are linked to IDILI, according to the Hamner-UNC Institute for Drug Safety Sciences. Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (SCARs) are rarer but even more terrifying. These include:- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) - painful blisters and peeling skin, often starting in the mouth or eyes.

- Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN) - a more extreme version where over 30% of the skin detaches, like a severe burn.

- DRESS syndrome - drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. It causes fever, swollen lymph nodes, rash, and organ inflammation - often the liver, kidneys, or lungs.

Why Do These Reactions Happen?

Scientists don’t have one single answer, but the leading theory is the hapten hypothesis. It goes like this: Some drugs get broken down in the liver into reactive chemicals. These chemicals stick to your body’s own proteins, turning them into something the immune system doesn’t recognize. Your immune system then attacks these "fake" proteins - thinking they’re invaders. The result? Inflammation, tissue damage, and organ failure. This explains why some reactions only happen after weeks. It takes time for the immune system to notice the altered proteins and ramp up a full attack. It also explains why certain people are at risk. If you have a specific gene variant - like HLA-B*57:01 - your immune system is more likely to react to drugs like abacavir (used for HIV). That’s why doctors now test for this gene before prescribing abacavir. The test is nearly 100% accurate at ruling out risk. But here’s the problem: HLA-B*57:01 is one of the only known genetic predictors for IDRs. For 92% of other drugs linked to idiosyncratic reactions, there’s no test. No warning. No way to know if you’re at risk until it’s too late.

How Do Doctors Diagnose Them?

There’s no blood test or scan that confirms an IDR. Diagnosis is a process of elimination - and timing. Doctors look for three key clues:- Timing: Symptoms start 1 to 8 weeks after starting the drug. Rarely earlier, almost never immediately.

- Severity: The reaction is much worse than expected for the drug’s known side effects.

- No other cause: No infection, autoimmune disease, or other drug explains the symptoms.

What Happens After Diagnosis?

The first and most important step: stop the drug immediately. Delaying by even a few days can mean the difference between recovery and death. Treatment is mostly supportive:- For liver injury: hospitalization, monitoring liver enzymes, sometimes steroids if inflammation is severe.

- For skin reactions: intensive care, wound management, IV fluids, and sometimes immunoglobulins or steroids.

- For DRESS: steroids are often needed to calm the immune system, and organ function is closely tracked for months.

Why Are These Reactions So Hard to Predict?

Because they’re not caused by the drug alone. They’re caused by the drug + your genes + your immune system + your liver enzymes + maybe your gut microbiome. It’s a perfect storm. Most drug trials are too small to catch reactions that happen in 1 in 50,000 people. Even post-marketing surveillance misses up to 95% of cases, according to the European Medicines Agency. Patients don’t always report vague symptoms. Doctors don’t always connect the dots. And here’s the brutal truth: we still can’t predict most IDRs. Only two drugs have reliable genetic tests. For the rest, we’re flying blind. That’s why pharmaceutical companies now screen for "reactive metabolites" - the dangerous breakdown products that trigger immune responses. In 2005, only 35% of drug makers did this. By 2023, it was 92%. Pfizer, for example, now rejects compounds that produce more than 50 picomoles of reactive metabolites per milligram of protein. It’s not foolproof, but it’s helping.

What’s Being Done to Fix This?

There’s real progress - but it’s slow. In 2023, the FDA approved the first predictive test for pazopanib, a cancer drug linked to liver injury. The test, based on genetic and protein markers, caught 82% of at-risk patients. It’s not perfect, but it’s a breakthrough. The NIH is investing $47.5 million into the Drug-Induced Injury Network to study how and why these reactions happen. The European Union’s "ADRomics" project is using AI to analyze DNA, immune cells, and metabolites to find hidden patterns. The goal? Predict risk before a drug even hits the market. The FDA plans to launch its IDR Biomarker Qualification Program in 2024. That means researchers can submit new tests for official validation. If approved, they could become part of standard care.What Should You Do?

If you’re taking a new medication:- Know the warning signs: unexplained fever, rash, yellow eyes, dark urine, severe fatigue, swollen lymph nodes.

- Don’t ignore symptoms that appear after 1-2 weeks of starting a drug.

- Keep a list of all medications you’ve taken - including over-the-counter and supplements.

- If you’ve had a reaction to one drug, assume you might react to others in the same class. Tell every doctor.

- Ask: "Is there a genetic test for this drug?" Especially if you’re of Southeast Asian descent (for carbamazepine) or have a history of autoimmune disease.

Sohini Majumder

November 29, 2025 AT 21:02Sara Shumaker

November 30, 2025 AT 10:31Scott Collard

November 30, 2025 AT 15:08Steven Howell

December 1, 2025 AT 01:08Robert Bashaw

December 2, 2025 AT 16:58Brandy Johnson

December 4, 2025 AT 01:39Peter Axelberg

December 5, 2025 AT 23:35Monica Lindsey

December 6, 2025 AT 01:35jamie sigler

December 6, 2025 AT 19:28Bernie Terrien

December 8, 2025 AT 00:29Jennifer Wang

December 9, 2025 AT 23:55stephen idiado

December 10, 2025 AT 02:58Subhash Singh

December 11, 2025 AT 00:09Geoff Heredia

December 12, 2025 AT 06:19Tina Dinh

December 12, 2025 AT 23:51